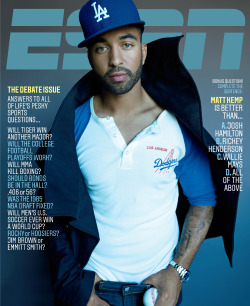

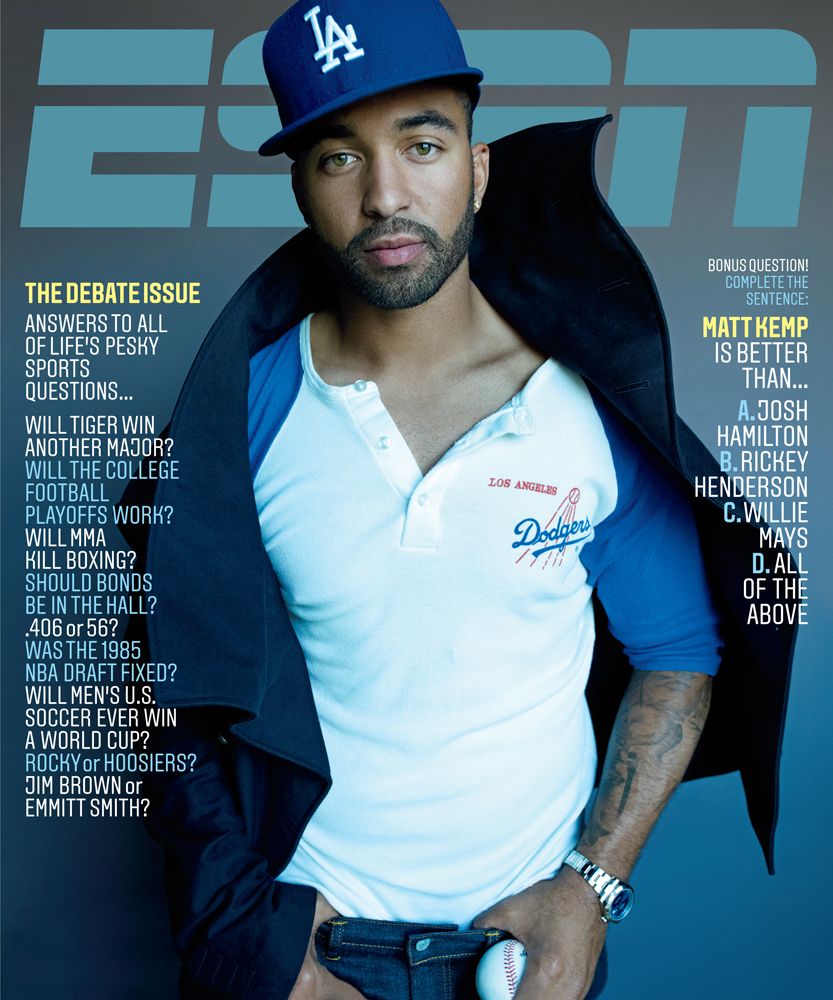

Matt Kemp cares. A lot.

HE IS OFF with the crack of the bat.

Andre Ethier smokes a line drive toward the wall in left-center, and though Matt Kemp has a small lead off first base, he thinks one thing: score. With his head down and legs pumping, Kemp is a blur in home whites as he rounds second. It's May 30, and he is only two days removed from a 15-day stint on the DL with a bum hammy -- but the duct-taped Dodgers improbably own the best record in baseball. Kemp is their leader, having mashed 12 homers in April and posting a video-game-like line that has people talking about the 27-year-old centerfielder as the player of a generation. And tonight, in the first inning of his second game back, he has drawn a walk. Now he has designs on home.

The trouble hits as he rounds third, the muscle fibers in the back of his left thigh seizing up again, slowing him to a trot. Kemp scores easily but walks back to the dugout a bit gimpy.

He knows this injury is worse than the first, but he descends the stairs and puts his helmet in its cubby and acts as if nothing is up. This is the attitude we've seen in the past. Placid, seemingly indifferent. That has been his MO since first reaching the majors, much to the frustration of veteran players, old coaches and the Dodgers front office: Matt Kemp was too cool to care. But his manager, Don Mattingly, knows better. He asks Kemp, "Are you okay?"

"I'm good," Kemp says, staring at the field.

Mattingly isn't buying it. "Matty," he asks, pressing, staring at him now. "Are you okay?"

Looking Mattingly in the eye, Kemp shakes his head. "No," he says. "I'm not good."

Mattingly pulls Kemp from the game, and now critics think they see what they've always considered the close cousin of Kemp's affected apathy: immaturity. He wheels around and throws his arms over his head in anguish. And when pacing the dugout fails to calm him, he grabs a bat, leaps into the air and breaks it over his right leg. He throws the barrel of it at the bench, disgusted, and as dazed teammates look on, he carries its severed handle down the steps to the clubhouse and slams it to the ground as well.

From the outside, he looks like the same old Kemp: a guy whose talent is as raw as his composure is unformed, beguiling fans with the preternatural ability he doesn't care to hone. But perceptions are deceiving with Kemp, especially of late. The harder the game treats him, the more he respects it, cares about it -- and the better he plays.

THIS WAS HOW easy Kemp had it: Baseball wasn't even his first choice.

Growing up just outside Oklahoma City, Kemp was a sophomore when his high school basketball team, the Midwest City Bombers, won a state title, led by Shelden Williams, the future Duke star and NBA veteran. By his senior year, Kemp was an Oklahoman All-City selection, averaging 20 points a game. He got some offers to play in college as a guard, but at 6'3" and not getting any taller, he realized his best shot at going pro would be on the diamond. He spent his senior year playing hardball year-round, the first time he'd done that, and scouts began turning up at his games. Kemp, a baseball player but not a baseball guy, assumed they were college scouts. "I had no idea you could get drafted out of high school," he says with a laugh.

The Dodgers liked his body: quick, strong hands that could catch up to any major league fastball and flick it over the fence, a cannon for an arm and those long, powerful legs that made him look like he could fly. The game could be learned; those tools could not. Despite the fact that he'd been playing baseball year-round for only a season, LA took him in the sixth round of the 2003 draft and offered him $130,000. That was more money than he'd ever seen. Though Kemp's father had been in his life, he was raised by his mother, Judy Henderson, a registered nurse. "We definitely weren't poor growing up, but we weren't rich," Kemp says. The bond they shared only strengthened when Kemp was 13. Judy had given birth to a second son, Tyler, who was born premature, weighing 1 pound and 1 ounce and without a set of fully developed lungs. But Tyler fought on well past any doctor's expectations. On the days that Judy would leave at dawn to be by Tyler's side at the hospital and not come home until after dark, Kemp got himself to school, did the cooking and finished his homework alone. When Henderson needed a soft word, Kemp was there. "If it wasn't for him, I don't know if I could have made it," she says. Tyler died shortly after his first birthday, but Kemp considered his brother the strongest person he'd ever known.

As a pro he excelled immediately, hitting 18 home runs in A-ball at age 19 and smacking 27 homers and stealing 23 bases the following season. Catcher Russell Martin spent some time with Kemp in the minors. Those were fun days, Kemp at one point cramming as many as five teammates in a three-bedroom house by partitioning off parts of the living room. Martin says Kemp was the self-conscious one, always dressing fashionably but quick to withdraw and fall silent when criticized. Martin remembers Kemp being so green he would be thrown out on the base paths standing up, but he was also the best player among them. "You just knew he could be a superstar," Martin says.

In 2006, just four years after he started taking baseball seriously, the Dodgers called up the 21-year-old Kemp. His first game was at RFK Stadium the afternoon before Memorial Day. "I'd never been in an outfield that big," Kemp says.

That year was Ned Colletti's first as Dodgers general manager. "When I got here, I saw a guy with more talent than most, who had probably played less baseball than most," says Colletti. "That can be a tough combination because you have great expectation, but you can't microwave experience."

The following year, Kemp hit .342 in 98 games. And in 2009 he hit .297 with 26 home runs and 34 stolen bases and led all major league centerfielders with an .842 OPS. He took home the Gold Glove and Silver Slugger awards and helped the Dodgers to the NLCS for the second year in a row.

But his gaudy numbers did not endear him to Dodgers veterans. In 2007, Jeff Kent chided Kemp and other young players for lacking professionalism and the desire to close out a season as strong as the Dodgers had started it. Dodgers infielder Nomar Garciaparra recalls a time he sat next to Kemp in the dugout and offered some constructive criticism: Kemp had all the tools to be an MVP someday, but he had to care enough to become one. "So many of us saw how special he was," says Garciaparra. "He'd listen, but sometimes he took it the wrong way. He'd take it like he must be doing something wrong, and he'd go into instant defense mode. It was sort of like him against the world."

ONE NIGHT A month into the 2012 season, with the Dodgers and Nationals tied at 3 in the bottom of the 10th, Matt Kemp takes a slow walk to the batter's box. The crowd shouts "MVP! MVP!" Kemp has hit 10 homers in April, four more than anyone else in the NL. He leads the league's batting race too, by 74 points, with a .452 average. And his 23 RBIs are one behind his teammate Ethier. Nationals reliever Tom Gorzelanny kicks the dirt on the mound, facing his plight with a look of practiced indifference. This night has belonged to Bryce Harper, the super hyped prospect who made his debut with the Nats, going 1-for-3 and driving in a run. But now Kemp is behind in the count, 1 and 2, against Gorzelanny. The lefty fires a fastball over the plate, and Kemp takes it deep and high into centerfield. The crowd follows its arc, screaming as it soars: a walk-off home run, Kemp's 11th long ball of the month, a Dodgers record. After Kemp touches home, he runs to the backstop and reaches for his mother's hand, grabbing it in celebration.

Two years earlier, with Kemp at his lowest, he had reached out to his mom too. He was hitting .230 through June and had gone into the defensive mode Garciaparra had seen earlier. If a reporter approached him, Kemp kept the answers short. Yes. No. I don't know. He let himself be misunderstood. "That was just out of frustration," Kemp says. "And not really being used to failure."

He was also not used to having his personal life scrutinized. He was 25, a pro athlete in LA with money in his pocket. He hit clubs like the Colony and Drai's and events at the Playboy Mansion. He was photographed around town as arm candy for Rihanna. But when his numbers plummeted, People magazine compared the couple to Jessica Simpson and Tony Romo. Everywhere they went in LA, the paparazzi followed, which only affirmed his critics' suspicions that he didn't care about his game. "My girl has nothing to do with what I do on the baseball field," Kemp said at the time. "If anything, she helps. She makes me happy. And as stressed as I am coming home sometimes, it's nice to have someone there who just wants to support you."